Vegetarian Food Poisoning

Only in this pain can I find relief in writing. My head does not find sense in the extreme heat of the flesh surrounding it or the spasmodic cold shivering of my hunched and drained body.

I am too weak to negotiate these contradictions and I am starving, but nauseous. Dare I eat? Vomit has not erupted like my tears nor launched out of my mouth the way these words have.

You found it odd for a healthy vegetarian to suffer from food poisoning. I hadn’t energy for self pity then, years ago, when I visited you in your new home of Montreal. The sickness worked through me as we prepared to cross the border back into the United States. Sicker, I became, as you told me of the time you were detained and interrogated for eight hours by U.S. immigration agents patrolling the same border with fearful suspicion of your brown skin. Not long after, you discovered your prostate cancer, indicated in a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test that registered a positive reading nearly double your age; uncommon for a 46-year old man.

Scores of articles discussed men in their sixties who were alarmed to find out that their PSA levels climbed over ten, since the usual level is less than half of one percent. Why your doctor had never screened you before was a mystery, especially since he knew of your mothers death from cancer, your father’s cancer, your brother’s cancer.

The jury found no reason to award you even a mention of sympathy in the ensuing malpractice case against your former doctor, your former friend; no one found it unsettling that his insurance company’s spies stalked you from Columbia Presbyterian Hospital to Mount Sinai Hospital to specialists outside of New York, who celebrated your sojourn with news of osteosarcoma, and a prediction of only two more years to live; two more years of your own private summer—hot flashes from anti-testosterone medications. My twisted mind convinces me to laugh as I conceive you to be a feminist so dedicated as to challenge yourself to endure menopausal symptoms.

What happened? Will knowing change anything? Was it growing up poor in the rust belt of Michigan, breathing and drinking the metal industry’s toxic waste, in particular a substance so poisonous it was sold as rat poison, that, in the 1940s was added to the drinking water first in Michigan. Was it fluoride—a known carcinogen with no value in preserving teeth as government and big business would have us believe?

Was it eating sugar, saccharin, aspartame, or hormones and steroids poisoning already harmful milk, pork steak, chicken—just as any american has? Of all of the antibiotics produced, the most are consumed not by humans, but by chicken. Poultry has long been accepted as a meat meal “safer” than other dead animals, such as bovine growth hormone-injected cows whose milk contributes to premature puberty in gyrls—gyrls who develop breasts and menstruate at six years young.

If food comes from a house of slaughter, how does it keep you alive? But you used to be a vegetarian, so I will not indulge disrespect with naivete you already lived through. And I am sick again with food poisoning, days after you called from Canada to tell me that your younger brother learned that he too has prostate cancer, and that he wants to die.

You, who have completed months of ineffective radiation treatments and had thousand-dollar chemotherapy injections offer comfort and faith. He has no interest in survival, of reassurance of genital tumescence, or that your dreads have only lengthened (although they still require what you refer to with a giggle as “original color restoration”). This was not a time to rehash dismissals of holistic protocols or pursue talk of your inability to sleep or ask about unbearable pain that you would not speak of.

Secretly, I plan instead to send you antique Japanese handkerchiefs for your night (and day) sweats, Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals, and a bottle of Dark And Lovely, packed in heart-shaped, quilted Valentine’s chocolate boxes, cushioned by dry rose petals. This source of pleasure provides me with enough vision to steer me through my migraine headache to the kitchen, where I toast a piece of wheat-free, yeast-free, sugar-free cinnamon raisin bread. One of the raisins singes on a hot orange wire in the toaster, and I abandon the anxiety preceding the potential trauma of nibbling through stomach convulsions in exchange for the knowledge that, although being in pain saps an enormous amount of energy, surviving this only requires an additional investment.

When you depart from this earth, you will rest with the understanding that love has been your strongest resource for survival. All of the love in the world may not save you. And all of the tears in the world will not bring you back. But I still love you. I still cry for you.

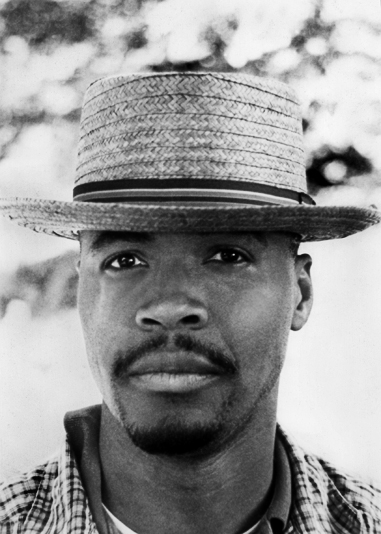

Elbert Nathaniel Gates: November 14, 1954-January 8, 2006